Abalone have long played an important role in the cultural and ecological history of California. They were a favorite food and decoration for coastal Native American civilizations for thousands of years. In the 1800s and early 1900s, Chinese and Japanese Americans introduced new abalone harvest methods and technologies that contributed to the popularity and robust culture of abalone harvest in California today.

Unfortunately, decades of heavy fishing and disease have taken a harsh toll on California’s seven abalone species. Today, commercial abalone fishing in California is not allowed at all, and only a single recreational fishery for red abalone remains north of San Francisco. In 2001, the white abalone was the first marine invertebrate to be federally listed as endangered due to declining population numbers, and black abalone followed in 2009. All of California’s abalone except red abalone are now either listed as endangered or considered a Species of Concern by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

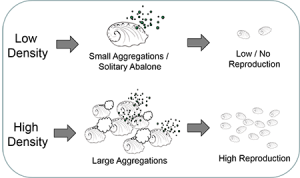

The white abalone, more delicate than any other abalone species, is in particular peril because scientists have found no evidence of natural reproduction. Low numbers of abalone in an area can bring reproduction to a standstill because abalone must be grouped close together when spawning occurs. Abalone of both sexes release their eggs or sperm into the surrounding water while spawning. Fertilized eggs develop into tiny swimming abalone larvae, but only if the eggs and sperm meet. If the spawning animals are too far apart, then reproduction might not occur. Today, wild white abalone are so far apart that scientists estimate there has been no reproduction in the wild for many years. So, even though some healthy adult abalone remain, the species is unable to reproduce and will go extinct without human intervention. The low numbers and lack of reproduction has made the white abalone functionally extinct in the wild.

Shortly before the white abalone was listed as endangered, a captive breeding program was started in southern California from eighteen wild animals. Unfortunately, a disease known as withering syndrome affected the captive breeding facility, and nearly decimated the captive populations.

In response to this event, two important things happened. First, the captive breeding program was moved to the University of California Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory (BML) where California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) abalone experts Dr. Laura Rogers-Bennett, Dr. Jim Moore, and Dr. Cynthia Catton provided invaluable guidance and support for the program in collaboration with BML’s Dr. Gary Cherr and Dr. Kristin Aquilino. Secondly, the White Abalone Recovery Consortium (WARC) was formed. The WARC is composed of multiple agencies and research institutions that have joined efforts and expertise to protect the future of the white abalone through captive rearing, restoration stocking, and public outreach.

This effort to restore white abalone populations is similar to the successful restoration efforts to enhance white seabass populations and save the California condor. The leading organizations within the WARC are NOAA, CDFW, and UC Davis. This strong, multi-agency and multi-institution alliance also includes public aquaria where many of the abalone may be viewed by the public.

The white abalone has several advantages over many other endangered species. Most importantly, their wild habitat remains intact. The number one challenge facing most endangered species today is loss of critical habitat. Additionally, the WARC team has successfully bred white abalone in captivity. So successfully in fact, that the captive breeding program is thought to contain more animals than all of the remaining wild populations combined. This success indicates that the captive breeding approach to restoration of the white abalone may be viable. There are many hurdles yet to overcome, but the captive breeding success means that the team can turn their attention to replenishing wild populations. A clear next step to restoring self-sustaining wild populations of white abalone is to introduce the captive-bred animals into the ocean.

CDFW and its partners are working hard to determine the most effective restoration stocking strategies through a series of field and laboratory experiments. In the last two years, CDFW scientists have led two experimental stocking studies with red abalone that will be used to identify optimal habitats and methods to move white abalone from the captive breeding program out into the ocean. With the successes of the captive breeding program at BML, and the critical work of CDFW in the field, we are getting closer to the ultimate goal of restoring the white abalone in the wild.

What can YOU do to help?

Learn More

We will continue to report on the exciting progress of these efforts through the CDFW Marine Management News blogsite and Facebook pages. For more information on the collaborative white abalone restoration project, check out our partner organizations as well!

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

- University of California Davis, Bodega Marine Laboratory

- Long Beach Aquarium of the Pacific

- Cabrillo Marine Aquarium

- University of California Santa Barbara

- Santa Barbara Natural History Museum Sea Center

Social Media

You can also help by following the CDFW and partner updates on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. Please, share with your friends!

In Person

You can also visit some of the captive-bred white abalone at the Cabrillo Marine Aquarium and the Aquarium of the Pacific in Long Beach and at the Santa Barbara Natural History Museum Sea Center.

post by Tallulah Winquist, CDFW Scientific Aid, and Cynthia Catton, CDFW Environmental Scientist

I’ve been going for Abalone for 35 years love the sport love what you guys are doing dive only Northern California how do you tell a white Abalone from a red I’ve never seen a white I don’t think

White abalone only live in southern California and Baja California, Mexico. They are very rare, and hard to find now. If you do dive in southern California, look for an abalone with pale tentacles around the “skirt” and bright white flesh showing through the holes in the top of the shell, as you can see in the picture above (in the article). Hopefully, you will have a camera with you so that you can take a picture of it and send it to us! Be sure not to disturb it in any way though, since it is a federally protected species. Thanks for your interest!

This is incredible research. Thanks for all that you are doing and I hope to be a part of an endeavor like this one day.